Danhauser’s Chess Game, Girl Power and an staggering amount of wrong assumptions in art criticism

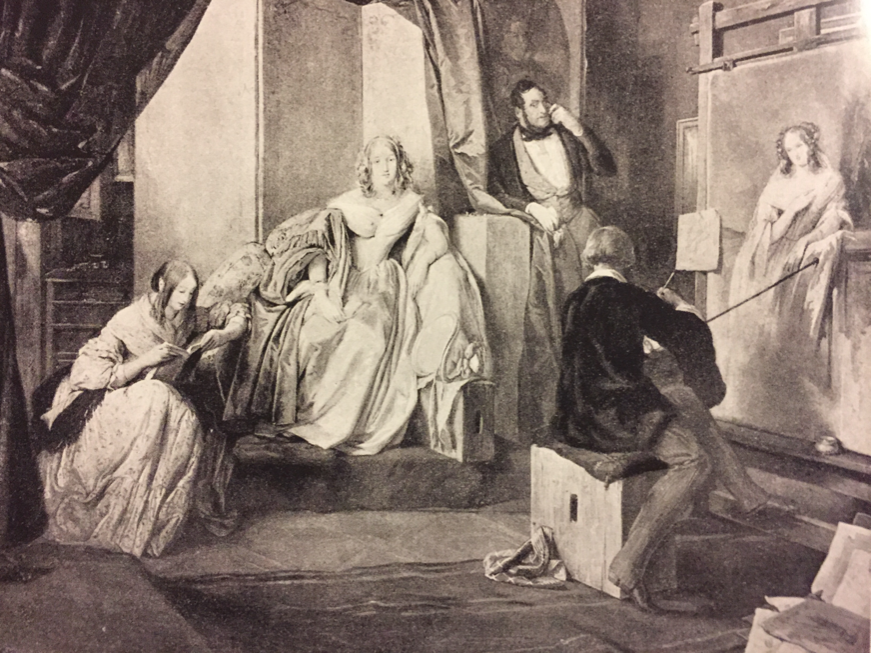

Last time I visited the Belvedere Museum in Vienna,* I saw this picture the Chess Game by Joseph Danhauser who lived from 1805 to 1845: the poor guy obviously had to share one normal human life span with Friedrich Schiller (1759 - 1805) or Admiral Nelson (1758 - 1805) and didn’t even die a hero like the last. This painting took me on a voyage of discoveries right through the world of art critics and their sometimes scandalously fictional “interpretations”. Here I wish to share these discoveries with you.

First I want to share my unreserved admiration for the outstanding skills so many artists possessed who did not make it into the art history books, who did not ride the waves or swim the currents that capture the attention of today’s specialists, such as ‘Mo-nay, Van Go or others who had any “low track to lose’. The mastership over his composition, the colors, the surfaces and substances I can almost feel, touch, the flawless mastership over the facial expressions, and the compelling logic of the action, which allows an art work to be turned into a short story: sublime! Granted, a Biedermeier painting like this may lack the romantic exoticism of a Delacroix or the fearful forebodings of a Caspar David Friedrich, and yes, compositions like this may remind of actors in a theater set, but let’s go with the flow and let ourselves be entertained by a piece of excellent theater captured in one split second chosen by the artist. Wasn’t Neuschwanstein, Bavaria’s famous Disney castle, now featuring on postcards over half the world, built by a set maker? Let’s enjoy the excitement, the drama, the silk dresses, the social undercurrents, immortalized in the refined, classy esthetics of a 19th century still under the spell of the post-Waterloo romanticism as it translated itself into the everyday life of the bourgeois rich. Let’s celebrate the apparent victory of Goethe’s Eternal Feminine narrated here. If I may compare the Biedermeier style shown here with the Blue Danube waltz, then we have at least the possibility of genius here also. Let’s follow the graceful half oval formed by the dark coats of the men and the nerdy woman around the bright satin of the victorious lady’s dress - starting at the seated old chess player, gently circling around, ending with the young man looking up in adoration - or taking the next exit via the blonde young man via the bearded man to the black stole of the second girl from the right, or to the statue (why don’t we color statues any more like they did in Minoan times?) - a bastion of male solidity, leaving the silken feminine frivolity in the western periphery, granted, but then unexpectedly finding itself penetrated by the victorious intrusion of the playing Lady’s splendid ivory silk, reflecting the score on the board (about that in am moment); or if you are Israeli, follow the line in from right to left, from the statue on the right toward the women in the west, looping via the pensive woman back to the loot on the upholstered stool. The beauty of walls, statues, paintings, human beings, clothing, fabrics, the fine filigree brush stroke (every description of a painting has the word brush stroke in it, so that’s done) minutely bringing out the shine over the silky gowns - the gleam on the Conrad Graf piano (at least I assume it must be a Graf, since Graf commissioned the Liszt Painting around the time this painting was completed; Danhauser also painted a portrait of this piano builder) with its brown varnish (when did pianos become black, and why?): I love this painting, the world of wonder it opens up to, the mystery of what takes place, the background stories to be guessed…

My discovery trip begins with a four and a half minute video I found on YouTube while browsing the web, crafted by a young and bosomy Hungarian art historian answering to the the Hungarian version of the name Lena Schwartz or Hélène Lenoir, or Helen African-American, perhaps (I googled Danhauser + chess game). After giving us some interesting and no doubt accurate information about the Biedermeier art style in a cute Hungarian accent, she comes with the story that this work depicts an actual event that happened a year before its date (1839), in which ‘a Hungarian noblewoman settled a debt that her lover had outstanding with the banker, whose name was Szklss or Essklss or something - when pronouncing unusual names, ar-ti-cu-late! - by winning this game of chess’. Ms. Elena de Arroz Negra de Nuestra Señora Maria Gil Torresano y Cuevas (when translating a name into Spanish you need to lengthen it) made clear that this painting, conform the Biedermeier style, was picturing actual people from Vienna’s society, friends and acquaintances of the painter, such as the young man with the laurel adoring the Lady supposedly being Franz Liszt. Since she failed to provide any more such identifications, I began an on-line search which led to three articles from 1905 by Julius Leisching, where the old man at the board was identified, not as Eskeles, but as Louis Pereira. The name Eskeles seems to belong to the painting The Family Concert, shown in the painting below, where I found him identified as the man seated in the middle under the statue of Cupid in adoring admiration of the singer, while I also found the young couple on the left wrongly identified as Robert and Clara Schumann: they apparently are modeled after the astronomer Karl Ludwig and his newlywed feminist author Auguste von Littrow, of whom D. made an almost identical portrait.

From that painting also comes the identification of the young blonde man leaning against the statue in our chess painting as violin celebrity Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst,* since the same model appears playing the violin in the Family Concert and therefore “needed” to be identified with the best known Viennese geiger of the time. These are all identifications I found in respected cultural magazine articles. Sabine Grabner, art historian at the Vienna Belvedere Museum which houses this painting, allows this character, who also appears in both versions of his Opening of the Will, to be a potential self portrait (you can decide, the drawing above is from 1830). I am not so sure, but I am loathe to take up my floret against this specialist, whose excellent book about Danhauser I managed to acquire on Amazon. Other identifications Leisching makes are the pensive Lady on the left as the painter’s wife (of her, a real portrait is given at the end as well); the woman leaning on the back of the old man’s armchair as ‘her sister Dichtler'; the man with the arms crossed is the deceased in the same 1839 Opening of the Will, appearing in the same pose on a painting within that painting; and the man looking at the board in excited disbelief may match a younger eye doctor in, well, the Eye Doctor. Before we further probe these identifications, let’s concentrate a little on these recurring personalities, types, leitmotifs, if you want.

Here on the left you find our young man leaning against the statue of Omphale (about her more in a minute too). I like to think of him as a girl in male clothes, like George Sand, though I think that such was certainly not Danhauser’s intention, and such delicate feminine features were a male beauty ideal in the nervous, poetic and over-romantic era of Byron, Mendelssohn and Chopin, before the number of musicians in orchestras grew into the triple digits and the entire male population, no matter what age, began to look like everyone’s great-grandfather. The middle picture is how the same model appears in the 1839 Opening of the Will, which I show at the end of this article. If you look closely at his eyes, you see that he is observing the reaction of the duped female descendant or listening intently and with only feigned indifference to the proceedings. The third representation is of course from the Family Concert, here above, which work is also called die Brautschau, (‘looking for a bride’). The fourth picture is from the 1844 version of the Will, where he left most of the characters the same. Also in the (earlier) Will, there is the portrait of the testator, the deceased, which more than matches the observing man in our chess picture behind the action. Now the question rises: would he really depict real people in such different situations? Was the man with the crossed arms in Chess really already dead?

Danhauser was severely criticized for thus recycling his characters, but don’t we all start from blueprints, like the characters in the Commedia dell’ Arte? Blueprints we find in musical melodies all the time. To the left are three examples by J.S. Bach, starting with the d minor prelude for (an instrument called) cello unaccompanied, followed by the very similar allemande from the d minor partita for violin ….

… and the also quite similar theme of the Musical Offering, officially attributed to Frederick the Great, who gave it to the old Bach to improvise on in 1747 in one of the rare encounters of two historical geniuses. My personal pet hypothesis that the melody was given to the king by his court accompanist CPE Bach who once got it from his father himself, has no evidence and is offset by the genius of this king, who wrote philosophy, composed good music, and was such a military genius that Napoleon, standing on his grave, claimed: if HE had been alive, I wouldn’t be standing here right now. Which reminds of Mozart deciphering Bach’s music in Leipzig in 1789, exclaiming: here is at last something from which one can learn! The theme is perfectly outlined, with its plaintive diminished 7th and its series of minor seconds:

Mozart had a preference for beginning a piece in A major from the fifth (E) with a downward motion to reach the ground A. It gives the feel of hanging in the air, gliding down to the ground. Something about A major must have given him that association, or at least something like it, because gliders didn’t exist in his time****, though hot-air balloons (Montgolfières) were introduced to the western world in 1783. We find this gimmick in his piano concerto K 488, his Clarinet concert KV 622 and Clarinet Quintet KV81, also his string quartet in A KV 464 (the KV numbers, from which you can recognize Mozart, are supposed to match the note examples):

What follows in the note examples is Mozart’s signature rhythm, with his name spelled backward (Trazom). Bruno Weil once plowed through all 104 Haydn symphonies and couldn’t find a single occurrence of this motive that’s in almost every first movement by his younger colleague.

Beethoven on the other hand sometimes begins a theme on the ground (tonic), then travels upward to the fifth, just to return immediately to the ground, which gives the melody a square, abrupt character, like an triumphal arch, falling well short of Mozart’s celestial melodies, as Beethoven’s third (op. 37) and Mozart’s C minor (K491) piano concertos show in juxtaposition. We also find it in the the G minor cello sonata (op. 5 no. 2) and in the Eroica (op 55 - I apologize, that’s musician’s shorthand to identify a piece: 55/1 = The first movement, Allegro con brio, from Symphony n. 3 in E flat major op. 55 by Ludwig van Beethoven. Classical music has such a lame nomenclature). On the other hand, Beethoven uses exactly this rude crassness to add a dimension of decisiveness we that makes his music so compelling. Elements of that brisk tendency also appear in his Triple Concerto (last example, left,) and his Ninth (last example, right), as I’m sure in many other instances. In the Triple it works to create mirth, in the Ninth it contributes the the irrevocability of the human condition as the master sets it in that glorious first movement.

Bruckner’s “mature”***** themes often combine triads and half steps. The triad paints nature, God, creation, things we can’t change; the half step reflects our feelings, pains, emotions (here on the left).

——-

Back to Danhauser. The statue in the painting (on the outtake on the left) has been universally identified as Omphale leading on Hercules, whom she had in her service as atonement for his having caused a wrongful death. That mythology I find fascinating in itself, it being an example of how mythologies appear to be formed around certain characters who become coat hangers for those themes: Iphigenia killed on the altar; Iphigenia saved at the last moment by Artemis and lifted up and away to become her high priestess in Tauris; Isaac killed by Abraham because he was the cause for Hagar and Ishmael being sent away******; then: nay, Isaac lives, his place at the altar is taken by a ram just like’s Iphigenia’s by a deer. We are all Cain’s descendants - wait, that’s too cruel, voilà Seth, so we don’t have to be Cains descendants after all - and no biblically attached Christian seems to have a problem with the suspicious similarity between the names of Seth’s descendants (Enosh, Kenan, Mahalalel, Jared, Enoch, Methuselah, Lamech) and Cain’s (Enoch, Irad, Mehujael, Methusael, Lamech). Also think of the three (!) times that a patriarch passes off his wife as his sister in Genesis, or how the stories of Utánapisiltem or however his name is, and of Deucalion and Pyrrha, resemble the story of Noah and the Flood (“So much for the unicorns; but from now on, predators lower deck, prey upper deck!”). Heracles is the proverbial man of excellence forced to do labor for his weaker neighbor. Someone who apparently liked to see a hero serving a woman, may have added that to Heracles’ story. Let’s enjoy the way she has her arm around Heracles, uncomfortable in women’s clothes, her confidence, her grace, her ease…

——-

That statue raises the first question about our picture depicting a historical event. Let’s look at an actual (semi-) historical event Danhauser was commissioned to portray: Franz Liszt playing the piano for his friends (1840, below). Here, in Liszt’s home or his study in Marie’s - which, by the way, is in Paris - we see George Sand (can’t miss …her? him?), the master, his girlfriend Marie d’Agout, Paganini and Rossini, Alexandre Dumas Père before he was père, a young Victor Hugo, a bust of Beethoven on the Graf grand piano, a bust of Joan of Arc and a portrait of Byron. Commentators have suggested the possibility of Berlioz instead of Hugo and Musset instead of Dumas, but Delpech’s litho after Maurin’s drawing of a young Hugo as well as Devéria’s drawing and litho of Dumas (see below toward the end) leave no doubt whatsoever - one advantage of the internet is the ability to pull up portraits by the dozen in no time. Danhauser uses outdated portraits of the famous individuals, who generally look about 15 years younger than they were in 1840. Maybe Danhauser couldn’t find a picture of Marie d’Agout, so decided to show her from the back. But here at least, every artifact, every music book, every book page painted has its place in Liszt’s home or Liszt’s room in Marie’s home.

What respectable banker in Vienna would have this statue of Omphale in his parlor? That, Mr. Darcy would say, is the material point.

The romantic young man on the footstool I found almost universally identified as Franz Liszt, probably because of the resemblance. That did make me uneasy. Liszt, the piano lion, the captain in the vanguard of the revolutionary Liszt/Wagner school, with his boisterous Hungarian rhapsodies and his Nietzschean, super-human symphonies commemorating Faust and Dante, two other symbols of pure masculine vigor, depicted in such an emasculating posture? Granted, the piano god could have been a submissive man in real life, his sexuality may have come from a different place - but representing that is not art, it’s family photo album stuff. Art is universal, it deals in images, not clinically diagnosed patterns. Chopin may or may not be correctly placed in such a pose, but not Liszt. No matter how he drank his coffee or cut his nails, Liszt, the beast, with his lion’s manes, must be the alpha dog.

More damaging to the hypothesis that real people are depicted here is Ignaz Franz Castelli’s review right after the Chess Game was first shown in 1839. If, as Ms. Ellen Ebony and a century of speculating specialists have it, Danhauser had projected real people eye-witnessing a real event, a true Wiener (sorry, Viennese) like Castelli should have recognized the individuals the way he and others did with the Liszt painting, which does have all real people in it. In our chess painting - set not in Paris, but in their own Vienna! - Castelli makes no mention of any real person whatsoever, and describes all characters in terms like “a man in his sixties”, “a beautiful Lady of 24 or 25 who must be a widow”, “a man who, judging from the medals he wears, must be a diplomate”.The supposed Liszt character he calls “an elegant, for sure a romantic, and a fervent admirer of the Lady, whom he had been watching throughout the whole game”, and “whose mouth can only utter super-sweet compliments”. He doesn’t even hint at a possible connection between the work’s patron and owner, Louis Pereira, who “graciously allowed the work to be visited at the artist’s house for another fortnight” - and the old man who just lost the game. Leisching, who was born 20 years after Danhauser’s death and probably never saw Pereira alive, makes this connection 66 years later. The statue of Omphale and Hercules, however, Castelli recognized immediately.

Three studies the author made prior to the art work seal the deal, and I am stunned how their significance for character identification could have been overlooked by a century of “scholarship”. At least one of those studies, on the next page, showing a Lady play against a bishop or priest, has been unanimously identified as showing a scene from Goethe’s play Götz von Berlichtingen (here on the right), where a Lady, Adelheid Waldorf, beats a bishop in chess, observing that her adversary “is not focused on his game”. A third character called Liebetraut is playing the cittern while singing, for the rest courtiers and court ladies. The combination bishop/lady/chess/minstrel/ courtiers makes the identification inescapable. To add my own two forints, in the second sketch, here to the right, where the Lady is in standing position, we see Franz, picking up up a chess piece the bishop had accidentally - or was it intentionally? - dropped … about which Franz later testifies that when his hand brushed against the hem of the dress, he got completely bedazzled and didn’t know how to find the way out of the room. In the third study, below, we see the scene moved from the 16th into the 19th century, and from a bishop’s palace to a patrician’s parlor. We see the pensive Lady and our supposed Franz Liszt already present.

This is my checkmate to the “real people” hypothesis. If an actual event were treated here, why do two studies depict a scene from a Goethe play? If I wanted to make a picture of the Browns’ perfect 2017 season in which they didn’t win a single game, would I start out with studies depicting Kirsten Dunst in Bring It On? If I wanted to glorify chess legend Judith Polgár making minced meat of some or other male champion, would I start out sketching Cranach's Judith with the head of Holofernes? Everything we know about this painting proves it is fictional, that Danhauser used people as models, and that the picture, with its Lady in dazzling colors, with its statue of Omphale, with the adoring elegant romantic, the stunned old man, even with the position on the board, where she plays black*******, tells a made-up story and tells it in an artistic, symbolic way, with everything pointing at the lady’s victory; and that even if the pensive Lady was painted after Josephine Danhauser or the romantic dreamer after Liszt, the characters are entirely fictional and have no bearing to the models used to create them.

Of all the authors I read on the subject, Sabine Grabner is the only one who rejects the untenable “real-people” hypothesis. She helped me clear my mind of today’s crazy and still popular 'identification frenzy’.

What would have been Danhauser’s inspiration? Adelheid von Walldorf in Goethe’s play is a dazzling, scheming, and eventually lethal woman. The play is a precursor of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung where a hero is destroyed by the political world. Adelheid is very much part of that world of gossip and intrigues. The first study shows the beginning of Act 2, a casual, matter-of-fact gathering of information for the rest of the play, when we see her playing chess against the bishop (“You are not very focused today”). The second study however shows a scene before that in Act 1, which we hear narrated by the young Franz describing the earlier game where he picked up the chess piece and his hand brushed against her dress. This poignant narrative must have attracted Danhauser. As the proverbial femme fatale, precursor of Carmen - they literally meet the same end! - he placed her in his own world, and created this immortal image.

Danhauser’s minute and detailed strokes allow a reconstruction of the final position on the board, (left), with the Lady, as stated, playing black. You can see that in this final phase of the game, the banker, who practically had the game in the bag, allowed himself to be surprised into a dumb-ass checkmate, by a mere pawn. Note as well that all three black pieces left are all situated on white’s territory, literally intruding in the man’s home, snatching away a world he had created for himself, just like in the character’s real life, where he loses God knows how much to a Lady in his own home. Danhauser approaches his theme from all possible angles…

Now for the picture. Julius Leisching counts 18 characters, Sabine 19, as did Castelli at its first review in 1839; and I 21 (that’s not Interstate 21, just that I identify 21 characters ;-): Sabine apparently includes the little hair bun plus neck to the right of the third standing lady on the left as a person, not a reflection; I take Sabine’s count and include the statue; which brings me to 13 women and 8 men. By the way - and I don’t think there is a soul in the world who has noticed this - the proportion female to male in the painting not only reflects the Golden Ratio point almost precisely, it reflects, in my count - I agree that the count is quite personal and disputable - an exact part of the Fibonacci series (1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89 etc. in which every next proportion approaches 0.618 alternately from above and below, each time more closely). Leisching’s count of 11 vs. 7 still comes to 61% women, and Frau Grabner’s 63%, while mine comes to 62%. In every count we have a majority of women, we have a a triumphant female victory in a game where the Queen is the dominant piece, as someone pointed out; we have a glorious Lady shown in the very center of the action, dominating the action in her dazzling, overbearing dress, that greatly overshadows every other gown (except one, in which her glory may be reflected, about that in a minute); and all this heavily ‘overscored' by the statue of a woman showing her full control over the greatest hero of antiquity. It is in this context that we have to interpret the adoring young man, our supposed Franz Liszt’s complete admiration for the Lady. The one male who can play the heroine’s counterpart is in full submission to her; the rest of the men either look like females or are stunned by them. Part of the Biedermeier is of course to show real people, not heroes, even if they are fictional. But we sure have a heroine here, reflected in two or three other idealized females. The role reversal initiated in the statue is completed in our praised, ‘laureled’ Mr. Mealy’s submission (liszt in Hungarian means flour, but about the meaning of composer names another time). This is maybe the secret message to the 19th century world of male chauvinism: follow the female principle, as art does, and help us make the world a better place. Was Danhauser thinking of the last line of Goethe’ Faust, published in 1832, where Faust’s soul is received in Heaven with the angels singing the redeeming words All things that perish are just an act; The inadequate, here it becomes fact; The indescribable, here it is done; The eternal Feminine, draws us in? (free after: me)

Alles Vergängliche - ist nur ein Gleichnis

Das Unzulängliche - hier wird’s Ereignis

Das Unbeschreibliche - hier ist’s getan

Das ewig Weibliche - zieht uns hinan

That our artist may have used the most masculine composer as a model for this message is irrelevant: the character shows the feminine, sensitive, romantic hero, no matter who may lay at the bottom of that creation. But there is more.

The loot shown below the chess board seems huge: money, deeds, maps of estates that clearly change hands at the checkmate. This means that the shock we see on many of the characters present shows perhaps more than mere astonishment. We cannot avoid the assumption that not one man but a whole family gravely suffers from the misguided choice of a possibly bewitched older male played by a cunning female. Is the pensive woman on the left a daughter? The concerned look of her friend suggests that she is directly affected by what’s taking place, though she could also be preoccupied by a private issue of which the friend informs her, as Castelli thought. Still, the more unified approach, with the more characters focused on the main theme, normally feels more rewarding in artistic representations (a form of Ockham’s Razor, I reckon). And what about the girl with the sad look on her face standing behind him? Why so sad? Next to her is the woman with the white hat - contrasting with the chess Lady’s black one - could she be … the mom? A closer look into her eyes reveal tears and great shock. The woman in yellow on the right doesn’t look quite happy either. The sad truth is that the Countess’ victory, though represented as the victory of the female over the male principle, probably still leaves women the main victims of the action: whether or not the artist with the laurels is a son, he will be all right; if the young man leaning against the statue is a son, he will have a trade; it’s the women who because of the dumbass actions of a doting idiot in a midlife crisis, have nowhere to go; and who see themselves, literally by one cruel move of a pawn, deprived of their chances to find a husband of quality. The first purpose, the “excuse” of a genre painting of this kind is moralizing: to show the evil of gambling without constraint. The inspired part here is the glorification of the Feminine. But in the end, it calls for compassion for women and the mindless, impossible position their society has put them in. How to deal with that? Danhauser doesn’t have the answer, he just shows the problem. And he sure had no idea that 6 years after this painting, his own widowed family would experience the same destitution hinted at here.

The Lady in the ivory or salmon or flamingo or crêpe gown on the right, next to the woman in the yellow, with her content look in her eyes and her Mona Lisa smile on her face, admiringly watching the triumphant Lady, is different from all other women in one other aspect also: her dress. The victorious Lady’s dress has that dazzling shine that could indeed make it a sign of nobility, though I have not seen any mention made of that by Castelli or any other critic of the time. But whatever the dress means - and I’m still searching - this admiring, excited woman seated on the right has almost the exact same attire as the victorious lady’s, her dress, her gloves, shawl and hat. And her eyes say: Good job, My Lady! I wonder if these two women are in league. Is she the Lady’s daughter? Castelli guessed the “mother” at 24 or 25, but was he right? Would they be sisters? Is the Lady a countess and the girl her first Lady in waiting, or however that’s called? I even wondered if both of them could be courtesans, - that would explain the splendid dress as well - and somehow got the old man to stake his fortune against their services; but that would hardly be likely with his family and so many other acquaintances around, would it? I wish I could read the meaning of their gowns. I am sure someone in 1839 could have told me more about what sort of women wore these particular gorgeous outfits. For instance, the initials on the victorious Lady’s glove, a sign of nobility, or just a mark of their particular local Mark & Spencer’s?

Where does Danhauser stand about women? A good number of men have fantasies about strong women. Like homosexuality, those could never be confessed anywhere in the past, so many artists - it’s natural to suppose a higher percentage of ‘submissive' men amongst artists than amongst neanderthals (except for artists among the neanderthals, of which we have little or no record - buried their fascination in their work. Homer has his foursome in the Odyssey, has Odysseus be prisoner of Calypso and his men all be changed into beasts by Circe: Nausicäa (“now ZEEkah-ah!”) leads the hero to her father’s palace. Virgil had his Camilla and so did Prince Charles; Bradamante her Ariosto or the other way round; Tasso his Clorinda, his Armida (next week I intend to discuss Tancredi’s intended life-long imprisonment in Armida’s castle by the mere click of a lock falling shut). In the Dream of the Red Mansion, possibly the greatest novel China has ever produced (available in quite entertaining English at Penguin Classics under the title The Story of the Stone - tr. David Hawkes), the maturing adolescent Baoyu (“pow yü” as Olivier Brault would say it when speaking English) exclaims how strongly women are superior to men (this is Baoyu speaking, not Olivier), and how much he just wants to live around them and serve them. Often submissiveness may result from a great admiration of women. I have seen between two and three hundred paintings of Judith with the head of Holofernes (I haven’t counted them, but I’m sure it’s more than 2 and less than 300). A quick internet search resulted in 21 separate paintings by Lucas Cranach alone, 19 of which in the same lugubriously attractive pose seen above (all right, I found 12 really by him, the rest were copies within his circle - but that’s not including the Salomes (9 & counting!), the Delilahs (3), Omphales (2) and his Phillis! Judith as slayer of Holofernes and Salome ordering the death of the Baptist is of course a place where the fascination with death meets the one with sexual attraction. Shudder… But what a count!

Danhauser was of course much more moderate. He may have been professional about his art. It is only on three or four occasions he seems to have seized the occasion, but those few times speak volumes. His Atelier with Joan of Arc has three women towering above their male partners: the model, with whom the painter apparently desires a connection she doesn’t share; Joan of Arc in his painting, gloriously taking possession of the painter as an opposing knight; and Saint Justina of Padua in the painting on the wall by Moretto di Brescia (ca. 1498 - 1554), whose life is described by Wikipedia with serious contradictions, probably because of a mixup with Saint Justina of Antioch; and who is being adored by the commissioner of that painting, as it was customary in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The lute player at the bottom left adds to the theatrical, dream-like mood of the picture. Would the artist be a self portrait? Possibly. I found an exquisite drawing of himself from 1830, the year of that painting, which I show in the carousel at the end. Just like in the Chess Game, in Joan, the power and the glory of women is complete. Incidentally, which painter has ever shown a bored model? Danhauser has made two unmistakable representations of that undoubtedly quite common mutual annoyance in a painter’s life, and they are both gorgeous women - the other one is in a lost painting called the Marriage Through Convenience, a sequel to the Family Concert, also below in the carousel (fortunately we still have a black and white reproduction, it must have gotten lost, as so much in WW2): the same (of course fictional) people are portrayed, now in a married state, according to Sabine, with the young betrothed now being the painter and his wife contently reading a book, while the singer is posing and bored, and her new husband - falsely identified 64 years alter by Leisching as Mr. Eskeles - being jealous. Here is Woman glorified in the form of the gorgeous dress of the model and the beautiful grace of her pose on the canvas: three gorgeous women, three less than irresistible men: the vague image of somebody’s ancestor, showing convention and cold family pride: one man expressing everything that’s hideous in a man, and one of whom we see the back. Showing bored models, wouldn’t that be breaking a taboo? The crumbling of the invisible fourth wall, that’s pretty revolutionary in 1839, I reckon… Yeehah!!!

Then there is Delilah (1835). By herself she doesn’t provide a strong argument for the artists’s submissiveness (with submissiveness I mean a desire to a deep connection with the other sex expressed in wanting to be owned by her; we don’t have words for these beautiful, life enhancing desires because it is only recently that we have become aware of them, they have been much too powerful in the past for us to conceptualize them in our limited consciousnesses),********* yet with the other evidence we may suggest that desire rather than custom or economics may have been the inspiration to this work’s creation. I like the juxtaposition of brute male force and delicate feminine charm very much. I also like Delilah’s tenderness. She is clearly of two minds, which makes her human, like the characters in our chess painting are human beings; even Adelheid in Goethe is human. And I do read in the composition and the expressions that she owns him, male force at the service of female polish: civilization.

Other displays of female superiority in Danhauser are George Sand in Liszt, where she, not the piano virtuoso, with her foot resting on a book used as footstool, is the center, that is, the middle, of the composition - a coded hint? A statue of Joan of Arc shows his admiration for that heroine once again. Marie d’Agout is separated from the group and sits on her own, and though she sits at Liszt’s feet and we only see her from the back, she is sprawling generously (szétterpeszkedett in Hungarian, with the many eh-s so typical for that labguage), her dress regally spread out. Other works with imposing dress drapery are the Congratulation, the Letter, the Family Concert and its sequel, the Marriage out Convenience, as we have seen, the Eye Doctor, Dichterliebe, one of the Wills, the Sleeping Party and of course the Rich Reveller. The sentence you’re reading now adds nothing substantial to the discussion.

Finally, we have one amazon of his, shooting an arrow - a sketch.

But there is more to Danhauser’s relation to women than just submissiveness. His studies are full of tenderhearted images of women. I chose the guitar girl in Wein Weib und Gesang, and, below, two sublime sketches for Chess. finally, his portrait of his wife suckling her baby, Motherly Love, simply defines tenderness (carousel). There is a collection of deeply empathetic works that portray sailors’ wives at the seashore during inclement weather, some with babies suckling, in fear and trembling for their husbands’ lives. Last but not least. he has two beautiful and humble Maries.

What fascinates me in the Game of Chess that lacks the wild suggestiveness of a Caspar David Friedrich or the profound emotional undertones of a Watteau, is the elaborate way the story is handled. There are simply so many sub-plots. One could write an opera in which the event is viewed from every single character, including the ones I have not touched on, like the nerdish girl (Mary in Pride & Prejudice), the ‘competitor’ with the folded arms, whom Castelli saw as an Englishman; or the grandson of an Irish immigrant who fought for Frederick the Great in the 7-years war before he was captured, brought to Vienna, fell in love with the daughter of his keeper, and settled forever in the Austrian capital (my elaboration). This grandson still has the red hair of his ancestors. Or who is the bearded man with the gold vest leaning against the right side of the statue, and where is he looking at? Does he reflect the clown in Shakespeare or the chorus in a Greek play, identifying the particular evil that we witness here? And what about the old lady, whom I thought was a male ancestor, part of the painting inside the painting, until my Marie pointed out that the hand with the glove, which is not part of that painting, cannot belong to the young lady in front of her because it is a right hand with the back turned toward us and the index finger up. But what is she holding between index and middle finger? A cigar? A brush or a pen? And the man who looks like Schubert and who checks the board in great excitement? Is he a scientist, or as Castelli believes, a diplomat, or just another banker, like I decided the man with the folded arms must be. What dreams were broken with that chess game, what desires fulfilled? We will always keep guessing. And that’s exactly why this art work will never stop to fascinate.

Notes

* I actually never went to that museum. My visits to Vienna have been limited to two or three afternoons over five decades. Alas!

** Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst was the man who rented a room next door to Paganini’s hotel room to hear the celebrated master practice, to get a view in his musical kitchen, and even pirated a new composition Paganini was practicing.

*** Some of those encounters are not even recognized today. While most people “get” the extraordinary quality of Bach’s work, most musicians I met have no clue of the genius of the Prussian king, so they completely miss this extraordinary moment. Let’s relish some other such great encounters: Schiller meets Goethe, an immensely beautiful story and the beginning in one of the most prolific friendships in history, with an equally intense ending when a now aged Goethe holds what he thinks has to be Schiller’s skull in 1828, and a breathtaking poetic fragment left of it; Napoleon meets Goethe, perhaps somewhat disappointing, geniuses are supernovas who often need their space. A young and upstart Beethoven plays for Mozart, of which we have, alas! too little to go on; T’ang poets Li Pai and Tufu usually considered China’s greatest poets ever, are known to have met a few times. Mendelssohn played Beethoven for Goethe, with exactly 60 years between the writer/secretary’s and the pianist/composer’s years of birth. G.B. Shaw and Churchill (“Come to my new play, bring a friend, if you have one” - “I’ll come to the second performance, if you have one”) gave us undying humor; as did, Einstein to Chaplin: “You don’t say a word and the whole world understands you” - Chaplin to Einstein: “You are greater: the whole world admires you while no one understands you”. Arthur Schnabel, the great pianist who we’ll cherish forever thanks the the gramophone, has been reported to tell Einstein, with whom he was playing through some violin sonatas, that ‘he could not count'. Finally, two extremely well-known people who never met, and I am ashamed for having to emphasize that to this day, are Richard Wagner and Adolf Hitler. The greatest composer of the 19th century (let’s call it from 1829 - 1928) had been dead for 6 years when the greatest monster of the 20th was born.

**** Would they have had paper airplanes at the time, or did the real planes have to be invented first before they got the idea?

***** When I say mature, I usually mean it, as opposed ‘mature audiences’, where it almost always means the exact opposite to what it says.

****** There is textual evidence that this may have been the original story: the part with the angel interfering has an idiom that does not occur in the rest of the story. Gen. 22:19 mentions Abraham returning but without Isaac being mentioned (!). Also, what has Isaac been reported doing after the trip to Moriah? Blind, crippled …

****** Please allow me the obvious statement that racism has no place in this discussion. The color black in a dress or a chess piece has absolutely nothing to do with the skin color of African decent, just like the color white in snow or bird poop has nothing to do with mine. The color black in European culture, the color of the night, expresses the sinister, the mysterious. To read racism in that is racism itself, it violates living identities of our inner selves, and takes the deepest spiritual and universally human foundation out of our culture, one of the most humane cultures in history, but most importantly, the one we live in right now. The color black has nothing to do with African Americans.

********* Submission of a woman to a man has of course long been recognized, cherished and institutionalized

P.S.: Would anyone still have any doubt that the characters in the Liszt painting are a young Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas? The Hugo etching below is after Nicolas Eustache Maurin, the Dumas should be a litho by Achille Devéria, which Danhauser almost certainly used - it’s very close to a drawing by the same. Why is this still disputed?

Illustrations:

2 - Schloß Neuschwanstein (=New Swan Stone), Füssen, Bavaria. I don’t believe the Swan is a reference to Wagner, whom king Ludwig II, who built the castle, admired; the old castle near it, Hohenschwangau, also has the word swan in it

3 - Self portrait, drawing 1830;

4 - Family concert, or die Brautschau (‘Bride search’ 1841);

5 - Details from Chess (1839), Opening of the Will (1839), Family Concert (1841), Will (1844), Chess, Will (1839);

7 - Franz Liszt at the piano (1840). This was the next work Danhauser painted.

8, 9, 10 - Studies (I believe no. 1, 2, and 3, in that order) for Chess;

11 - The Board from Chess; diagram of the position on chess board

12- Lucas Cranach the Elder., Judith from 1. Vienna; 2. New York MET; 3. Kassel

13 - Samson and Delilah (1835)

14 - Study for Wein Weib und Gesang (1839); Study of an amazon (unknown)

15 - Two studies for Chess

16 - Portraits of Hugo and Dumas from Liszt at the Piano compared to their originals by Nicolas Eustache Maurin and Achille Devéria

Carousel (click on the right of the image to get the entire next picture etc.):

1. Artist’s Atelier with Joan of Arc (1830); 2. In the Artist’s Atelier or The marriage out of Convenience, or the Envious (1841); 3. Motherly Love (1839); 4: Opening of the Will (1839): 5. Opening of the Will II (1844); 6. Bluebeard with his Last Wife (my title), by Achille Devéria, whose portrait of Alexandre Dumas is shown above. I included this just for fun.